The Agony in the Car Park

Newcomers to contemporary art often complain it’s daunting (one of my students recently applauded the value of “collective brainstorming” to arrive at some kind of understanding) so it’s very satisfying to be able to recommend Grayson Perry’s The Vanity of Small Differences at Victoria Miro. Proof that contemporary art can be accessible and sophisticated.

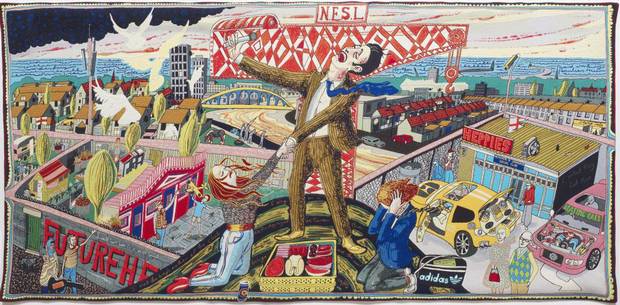

Perry’s 6 tapestries were partly inspired by Hogarth’s darkly comical The Rake’s Progress (1732-33). They tell the story of Tim (rather than Tom) Rakewell’s attempts to transcend his working class origins. Our geeky anti-hero – Sunderland boy makes good – goes to university, marries a middle-class girl from Tunbridge Wells (a den of sexual depravity in Restoration England but now home to Disgusted Of Middle England), sells his software business to Richard Branson, evades tax, buys a mansion in the Cotswolds, has a mid-life crisis, marries a leggy blonde called Amber, drives a Ferrari – too fast – and dies in the ensuing crash (car, not stock market). In my version, Tim’s trophy widow keeps his ashes in a Hirst-designed diamond-encrusted casket. Throughout, his progress is mirrored by the Hogarthian dogs: sometimes hybrid breeds, yapping or growling or ripping like Cerberus…England’s gone to the dogs.

Each tapestry is interwoven with quotations, texts, characters encountered during the course of Perry’s “taste safari” for Channel 4’s three-part TV series entitled (with a nod to Kenny Everett?) In The Best Possible Taste in which he immersed himself in the rituals of the working, middle, and upper classes. Part One saw him donning fake tan and big hair to go on the lash with a group of Sunderland girls where he learned the difference between tacky and classy dressing: it’s tits or legs, never both.

There are several similarities between Hogarth and Perry – their incisive use of humour; working class origins; an emphasis on Englishness; their theatricality; the use of visual and verbal puns; the references to other artworks within their own work (the tapestry titles give you a clue The Adoration of the Cage Fighters, The Agony in the Car Park, The Expulsion from Number 8 Eden Close, The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal, Lamentation; there are nods to Sigmund Freud, Van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Mantegna, Gainsborough et al). They also share an interest in taste. The Rake’s Progress anticipates Hogarth’s glorious Marriage a La Mode series where the artist railed against the British taste for French and Italian fashions (though this didn’t prevent him from using French engravers); in The Vanity of Small Differences Perry confronts our comparable class snobberies: everything from a love of designer labels to a suspicion of art. Perry lampoons the upper classes in The Upper Class at Bay or an endangered species brought down but reminds us: no matter how rich Tim becomes, he will never ever be one of them and, oh the irony, many of them – like Hogarth’s Earl Squanderfield – are skint.

At Victoria Miro on Thursday night there was bashful laughter when Perry (fabulously attired in frock and lippy by the way) spoke about “the guilt of the middle-classes.” Yes, they (you? us?) with their multiple coffee-making machines, dinner parties of Jamie Oliver meals and inherent paradoxes – recycling bins as a kind of trade-off for the environmental unfriendliness of the obligatory Aga. How ironic – again – that the eighteenth century poor recoiled in horror from rye and wholemeal breads, aspiring to the basic white loaf of the rich.

Grayson Perry at Victoria Miro Photo: Paul McCormick

Grayson Perry at Victoria Miro Photo: Paul McCormick

I asked Perry about empathy. Hogarth betrays no sympathy for any of his characters in The Rake’s Progress – even the hapless Sarah is at fault for being such a doormat (or what psychobabble would label an enabler). Perry could have been cruel but there’s genuine warmth in his work (compare it to Paula Rego’s equally superb take on Hogarth’s Marriage a la Mode for instance which is more disturbing than the original). Perry’s response was that he didn’t want to repeat Hogarth. That would have been boring. He wanted to confront his own prejudices about taste; prejudices, he admits, that may derive from the middle-class art world. He says he feels “very comfortable” in that milieu now – perhaps Hogarth never did given the Academy’s snobbery about his “vulgar” subjects. There’s a chameleon-like quality to Perry. I suspect you could put him in any situation and he’d instantly see how to behave and that only comes with empathy.

Richard Godwin enacts a good semiotic analysis of The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/arts/visual-arts/perrys-portrait-of-bourgeois-britain-7830941.html and it’s clear Perry uses contemporary symbols – the i-phone, the tweeter – to question societal attitudes to communication and consumerism. But aside from the richness of their content the tapestries are also beautiful as objects. Epic in scale (200 x 400 cm), their colours are intensely vibrant; they’re sophisticated in their use of pattern. See how the fragments of text yard working families loop into waves in The Agony in the Car Park – like relics lost at sea. You just have to watch Perry draw in In The Best Possible Taste to see he’s a draughtsman. With a few deft lines and a squiggle of colour, he captures an entire persona.

There are many parallels between the eighteenth and twenty-first centuries (the so-called social problems of alcoholism, the cult of celebrity, the increased dissemination of information through the media, the widening gap between the haves and have-nots, even plagiarism). On the whole though, the eighteenth century was a time of prosperity and of slavery-built empire. (Bizarrely the English were lauded for being the cleanest people in Europe after the Dutch.) And what it didn’t occur to me to ask Perry is: is a tripartite division of class still relevant? Or is there a fourth “class” of generations of unemployed who are evolving their own taste and if so what is it?

Perry chose his medium carefully. Traditionally, tapestries were the preserve of the very wealthy. They were hung on walls to provide decoration and to insulate those cold castles. Relatively portable, they suited the itinerant lifestyle of the lords of the manor. Hogarth did something similar when he made oil paintings. He wanted the English to buy paintings that reflected contemporary life. He was disappointed. Though the engravings were hugely popular with the middle-classes, the oil paintings had to be sold at a reduced rate. Those who could afford them couldn’t quite bring themselves to accept these were subjects for painting. I don’t think Perry will have the same problem.